Trump wants to rule the Federal Reserve

Jerome Powell and the Fed Governors are the last, and perhaps the most important, adults in the room.

In 2018, Donald Trump selected Jerome “Jay” Powell to become the new Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.

Now, Trump wants him out.

Trump’s displeasure with Powell has been brewing for a long time. Trump wants Powell to act to lower interest rates. As a lifelong real estate investor, Trump is conditioned to want ever-lower interest rates, especially since he currently holds large real estate debt and would personally benefit from lower rates. Lower interest rates would also “heat” the economy, and perhaps paper over market volatility and the real world hardships Americans are sure to face soon, all caused by the self-inflicted and rapidly worsening damage to our international trade partnerships.

Powell, however, is taking a much more careful and measured approach to monetary policy due to the economic uncertainty around tariffs, and this angers Trump. As an independent agency, the Federal Reserve is designed to act without political pressures. All of Powell’s recent public statements indicate that he greatly values this independence and takes his role as a nonpolitical central banker very seriously.

Powell has made it very clear that he will not bow to Trump’s pressure campaign to get him to resign, nor does he think he can be forced out.

There is at least one moderating voice in the White House. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is trying desperately to convince Trump that Firing Powell would be a terrible idea.

Under the Federal Reserve Act that established the Federal Reserve in 1913, the Governors of its Board can only be fired “for cause,” including the Chair. Trump has already been testing the limits of his power to fire staff he doesn’t like at supposedly independent agencies. Trump has fired two commissioners of the Federal Trade Commission, a member of the Merit Systems Protection Board, and a member of the National Labor Relations Board. A panel from D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals has ruled that the MSPB and NLRB firings were legal, but in a rare event, their ruling was overruled by the full membership of the Circuit Court. In yet another twist, Chief Justice John Roberts of the U.S. Supreme Court has stayed that second appeals ruling, meaning that for now, Trump is allowed to move forward with the firings.

These independent agency firings are being watched very closely. It’s widely believed that Trump has used these tests of his power to lead up to an ultimate firing of Powell.

Powell does not believe that a ruling from the Supreme Court in favor of allowing these firings would necessarily apply to the Fed—a strong signal that he will litigate any attempt by Trump to fire him.

Here, again, is Powell himself addressing the issue of threatened Fed independence:

The Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System is a distributed system of regional banks that make up the central banking system of the United States. The Board of Governors led by the Chair (currently Jerome Powell) oversees the whole system. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) makes monetary decisions.

This is an important point: The Chair of the Federal Reserve Board does not actually make monetary policy decisions themselves. The FOMC includes all 7 Fed Governors, the president of the New York Fed, and a rotating set of four other regional Fed presidents. The Chair is certainly very influential among this group and leads the discussion, but they cannot unilaterally make decisions. Perhaps the most important function of the Chair is as a public representative—explaining Fed policy decisions to the banking community and the general public.

The terms of the Fed Governors are purposefully long: 14 years. This is supposed to help the Fed stay nonpolitical and maintain a long view of the economy.

So what does the Fed actually do? The Fed has what is known as the “duel mandate”: to ensure low unemployment and to stabilize inflation at a target level. Here’s a clip of Jerome Powell explaining the Fed’s mandate: Video

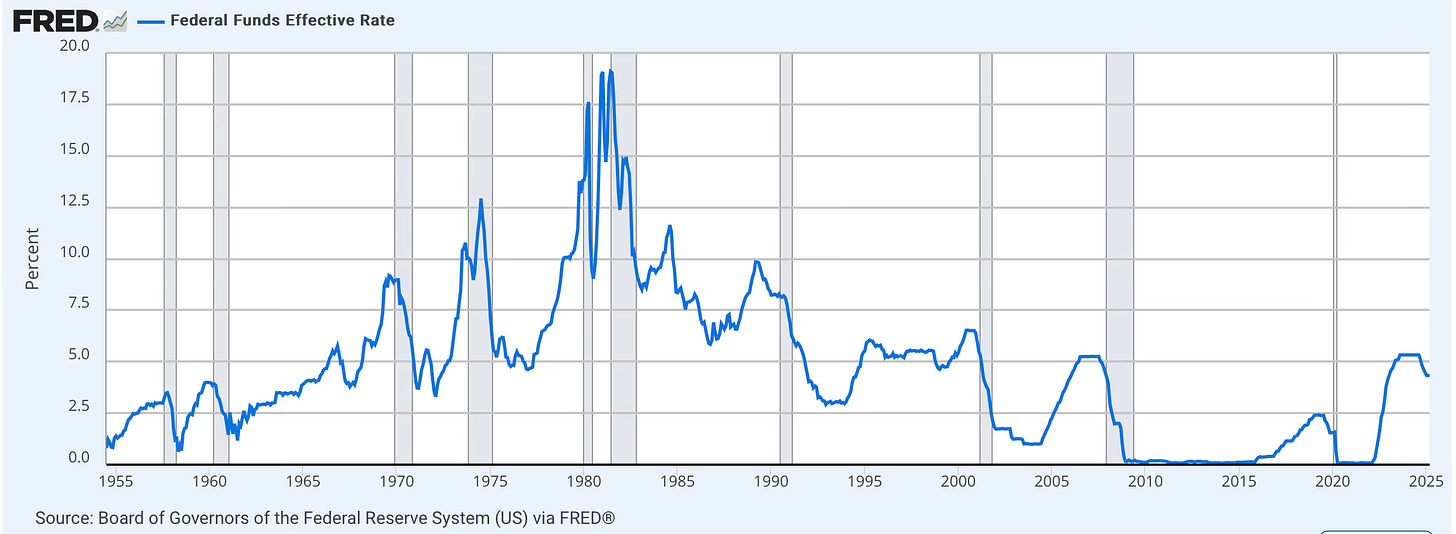

The Fed fulfills its mandate through monetary policy. The FOMC decides on a target “Federal Funds Rate,” which is the interest rate at which banks trade to each other overnight. Banks borrow from each other if they need additional liquidity to cover transactions. The Fed uses a set of policy tools to influence this rate. That interest rate then influences the rates at which banks issue loans to borrowers. Here’s the Fed’s own broad overview of its role in influencing monetary policy.

One inherent problem the Fed faces is that the tools to improve employment are the exact opposite of the tools that will reduce inflation. Normally, a contraction in economic growth (a “recession”) and the resulting unemployment come with reduced demand for goods and thus lower prices, so the tension between the two goals is not an issue. But sometimes, it is—and that is relevant to our current situation, as I’ll get into below.

Why keep Jerome Powell?

Why is Powell so revered and respected? Under his leadership, the Fed recently fought a period of rising inflation without sending the U.S. into a recession. That’s an extremely difficult thing to do, because as I said above, the tools the Fed has to fight inflation could easily slip the nation into a period of high unemployment. What Jerome and the Fed achieved instead was the “soft landing”.

There are reasonable critics that say the Fed was part of causing the rising inflation. To try to stave off an extended period of unemployment due to COVID, the Fed acted to increase the money supply, which can exacerbate the risk of dangerous inflation. The most extreme tools the Fed has to increase the money supply also inherently disproportionately benefit Wall Street. (This is a bit of an oversimplification, but because the Fed increases the money supply through banks, it relies on banks to “pass on” the money supply to borrowers.)

The Fed’s job is tough. Acting to save the economy from flailing in one direction can send it flailing in the other. I’m sure the Governors and other members of the FOMC wonder “what if” all the time. It’s easy to criticize when you aren’t in the hot seat to make the important decisions. And, because the Fed’s tools are limited, it needs legislative help from Congress and Executive leadership to ensure that efforts to stabilize the economy from the monetary side are matched from the fiscal policy side.

Politics, however, gets in the way of responsible fiscal policy.

Economic Fears around Trump’s Tariffs

A major worry with Trump’s tariff policy is that the magnitude of the tariffs and their highly volatile on-again, off-again rollout will lead to a protracted period of increasing inflation, and not just a temporary one-time price increase.

At the same time, the tariffs are likely to lead to a slowdown in economic growth. These two fears were voiced this past week by Powell himself. We will soon get Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data for Q1, which will tell us how much the overall size of the US economy has grown. Unfortunately, the latest estimates by the Atlanta Federal Reserve are showing a contraction. There are a range of model estimates, though, reflecting the high level uncertainty that has been recently injected into the economy.

If we experience both an increase in inflation and a contraction in the economy, that would be a massive problem for the Fed.

There’s a term for it: inflation + stagnation/contraction = stagflation.

Stagflation is the boogeyman of monetary policy because, as mentioned above, it’s really difficult for the Fed to deal with both at the same time. To control inflation, the Fed would raise interest rates, reduce the money supply, “cool” the economy. To encourage employment and growth, the Fed would lower interest rates, increase the money supply, “heat” the economy.

A former Fed Chair, Paul Volcker, faced a scenario of high inflation in the late 1970s/early 1980s. His response became known as “Volcker’s Hammer”: a drastic, rapid increase in the federal funds rate. In the chart below, you can see how the rate above 17.5% in the early 80s. Shaded areas are recessions.

You’ll see that the inflation and response correspond with recessions. It was a literal bear of a problem.

Powell is known to greatly admire Volcker, and he drew inspiration from Volcker to deal with high inflation after Covid. But, he also learned from the Volcker Fed’s mistakes/experience and achieved a “soft landing” rather than sending the economy crashing from high inflation into recession again.

Without a doubt, Powell is thinking about the stagflation of the Volcker era when he ponders how to deal with the potential effects of Trump’s shock-to-the-system tariffs (and overall poor international relations).

What does Trump want?

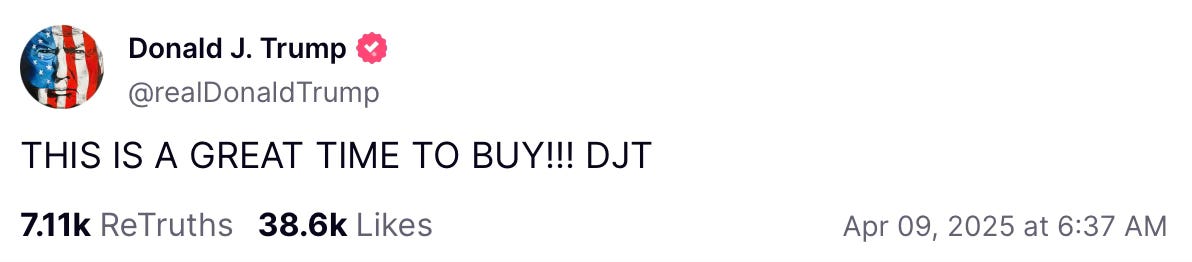

Trump wants the Fed to lower the Federal Funds rate.

Trump doesn’t seem to care much at all about the duel mandate and long term consequences of monetary policy. He’s been spooked by the immediate effects of his tariff announcement on both the stock and the bond markets (especially the bond market, which is much larger). Trump also likely wants the public to experience the frothy, money-rich times of an increased money supply (i.e., lower interest rates) to distract from the underlying damage the tariffs are doing. Remember, we’re not even seeing much the real effects on the economy yet—just fears.

Powell does not seem at all eager to get the Fed involved. It makes sense—any move the Fed makes now to lower interest rates to increase the money supply will hamper their ability to deal with the predicted inflation in the future. They want to see how the data plays out. I bet he’s even pondering an increase. It’s not worth it to the Fed to save markets before the real economic data comes in. Saving the markets is not the Fed’s mandate (although obviously they watch the markets closely).

Here’s a Powell clip explaining why the Fed won’t just step in to prop up the markets:

Essentially, he’s saying that market uncertainty is simply a result of real uncertainty. With expectations of slower economic growth or even a contraction, we would expect the value of companies (as expressed in share prices) to fall. Why would the Fed prop up a market that is acting somewhat rationally?

That clip was from Powell’s remarks and interview at the Economic Club of Chicago this past week. I encourage watching the full event. If anything, it’s quite refreshing to hear a real “adult in the room” address policy in a measured, responsible, and intelligent way.

Sidenote: Project 2025 on the Federal Reserve

Project 2025 has a lot to say on the Federal Reserve, and it’s pretty horrifying to most mainstream economists. According to Project 2025, the optimal goal is to get rid of the Federal Reserve altogether! Until that can happen it suggests removing “achieving maximum employment” from the Fed’s mandate and allowing elected officials to set the federal funds rate to address inflation alone. This would be eliminating the independence of the Fed.

(It’s interesting to note that Project 2025’s suggested policies would prevent the Fed from “printing money” by purchasing debt—one of the ways the Fed can act to lower interest rates. Trump probably would not like that.)

What Project 2025 advocates instead of a strong central bank is a “free banking” system, where banks are allowed to form and issue banknotes as monetary tender whenever they have assets to underlie those banknote loans—ideally gold. Market forces alone would regulate banks. In the ideal, there are many local banks, and fraudulent or incompetent banks would be driven out of business because they wouldn’t be able to compete for customers (never mind the customers who had to learn the hard way first, I guess). Perhaps even more relevantly, small free banks can be very vulnerable in economic downturns without collateral restrictions. Advocates of free banking argue that this system is more stable than our current system, subject to regular business cycles of expansion and correction/contraction.

But contrary to what free banking-enthusiasts believe, their system is still subject to cyclical failures and panics, just like any monetary banking system. Many banks in the US’s “free banking” era of 1837-1862 failed, as did many loosely regulated banks between 1862 and the creation of the Federal Reserve. Proponents of free banking argue that these banks weren’t really “free” banks because they were still often subject to requirements—and that their banks would be different this time.

Mainstream economists simply note that the modern era of central banking in the US has provided better economic security relative to eras without a central bank. Although we still experience economic downturns, the recessions and deflationary periods of the 1800s and early 1900s were of much greater magnitude than those of today (with the exception of the Great Depression, when modern central monetary policy for the US was still limited and experimental).

This is not to say that the Federal Reserve is perfect, or that there are no valid critiques of its policies and actions over the years. It’s just that regardless of all complaints and critiques, the overwhelmingly mainstream view among economists is that the Federal Reserve—the central bank—stabilizes the economy. Opinions to the contrary are loud and, for the moment, influential, but they are few.

What to look forward to

The chattering classes think Powell’s days are numbered. The practical effect of losing Powell would actually be somewhat minimal. Again, Fed decisions are made by the full FOMC. Trump would have to replace or improperly influence all of the Fed Governors on the Board to guarantee his preferred outcomes on FOMC votes.

But Powell is a highly esteemed central banker. This is the case within the Fed itself, among other international central bankers, and, critically, among business leaders and banking firms. He is widely viewed as the glue holding the US economy together as it gets hit with massive policy changes from the Executive branch. Without Powell, we’re likely to see a massive loss of confidence in the US economy and US assets (i.e., US Treasury bonds that fund our national debt). Interest rates on the secondary bond market will rise, making it more difficult for the US to fund its debt. The stock market may be pumped a bit by a new Fed that follows Trump’s whims and lowers interest rates, but that will be transient as the tariffs translate into realized losses for companies.

We’re already seeing the real effects of tariffs. Container shipping is already reported to be greatly reduced. Companies that sell in the US cannot afford to onshore their goods from China (obviously a major exporter to the US), so they are canceling shipments or letting them sit, hoping for a reprieve from tariffs. The waiting is costly as well—every business will tell you that uncertainty is expensive. Because there has been no additional stimulus of onshore manufacturing or time to allow onshoring to happen, I have to think that there will be goods shortages and price increases.

We will see this hit US companies materially. It is “earnings” season for Q1 2025, when CEOs give updates on company financials to shareholders and provide expectations for the upcoming years. United Airlines made waves this past week by issuing a highly unusual report that presented two outlook scenarios: one considering recession and one without. The admission of uncertainty to shareholders is striking but understandable. NVIDIA, one of the “big boys” in the market these days, announced that it will make a $5.5B charge due to restrictions on trading with China. Then, Intel announced that it will face similar restrictions.

The reason why the Fed is reluctant to prematurely step into this looming economic crisis boils down to the fact that this isn’t really an economic crisis. It’s a political crisis, and none of the tools at the Fed address self-inflicted, politically-driven, economic downturns. The US economy was pretty fine before Trump took office. Prices were high to consumers because we had just exited a period of high inflation. But inflation was under control and employment was high. Sure, there were and are still problems with affordability (life is hard for a lot of Americans, and they should be helped with proper policy!) but nothing Trump has proposed or enacted will help. In fact, Trump has inflicted potentially mortal wounds upon the mythical ever-growing US economy. Hence my referral to this as a political crisis. Politics are causing the economy to teeter. Monetary policy can’t fix politics.

Who can fix this looming disaster? Congress. Even if the courts allow Trump to fire Fed Governors, Congress has the power to rein Trump in. The easiest path of course is for Congress to simply take away Trump’s economic levers, like these tariffs issued under very specious claims of “emergency”. The tariffs could be over in literally the time it takes to do 2 ten minute votes. If the tariffs themselves anger you, then the ease with which they could be ended—but aren’t—should infuriate you.

The impeachment-and-conviction route is always on the table, too… there’s plenty of evidence of stock market manipulation recently, and Trump has the ultimate insider information. That’s called a crime. Majorie Taylor Greene made a killing. It’s not like he’s trying to hide it:

Trump doesn’t usually sign off with his initials. DJT is the ticker for Trump’s crypto. Always be selling, I guess.

Stay in there Jerome and fight

That was an excellent primer on the Fed, thank you. I am reminded of Andrew Jackson's war against Nicholas Biddle and the second Bank of the United States. Donald Trump is known to hugely admire Andrew Jackson and even had a portrait of Jackson hung in the Oval Office. Just as Biddle was Jackson's bete noir, so has Powell become Trump's obsession. History repeats itself once again